[For an earlier post on science and art: exploringtheheartofit.weebly.com/blog/mutual-inspiration-science-and-art]

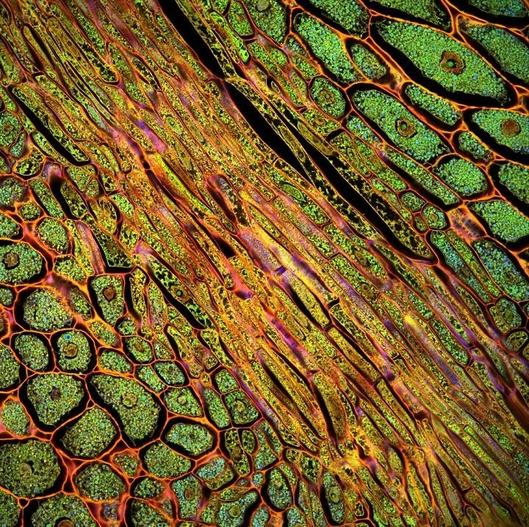

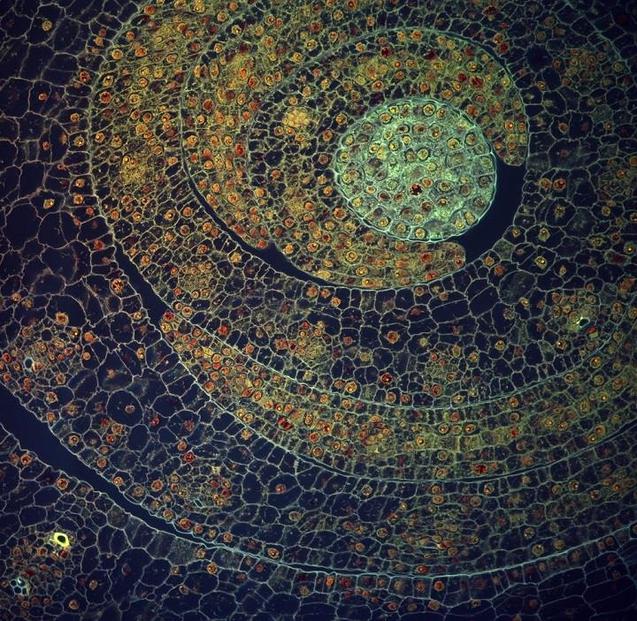

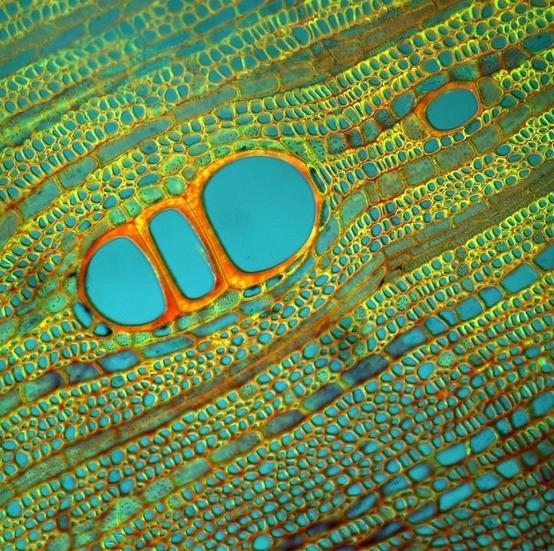

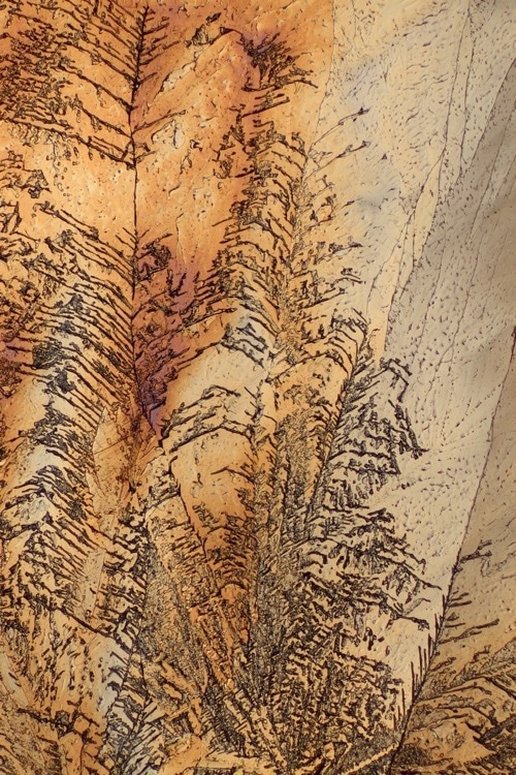

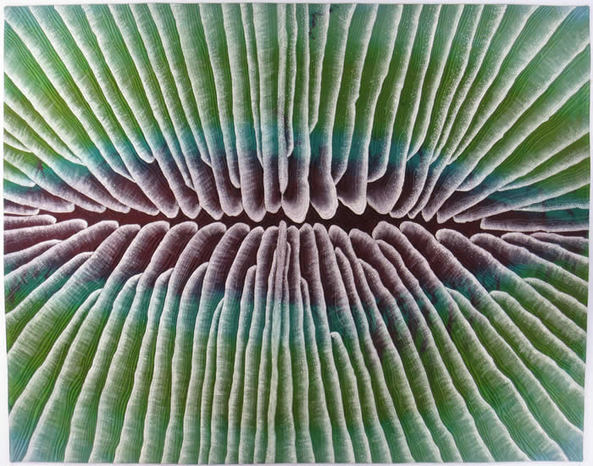

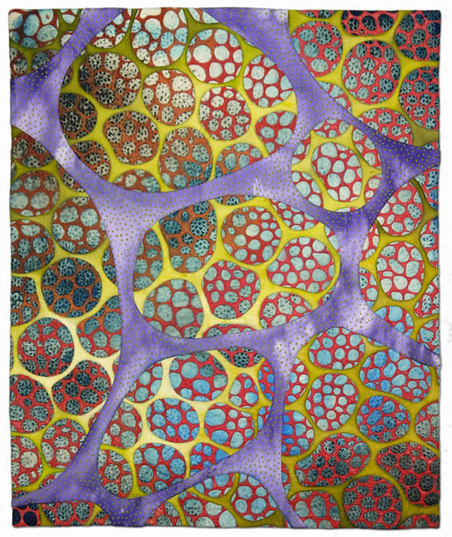

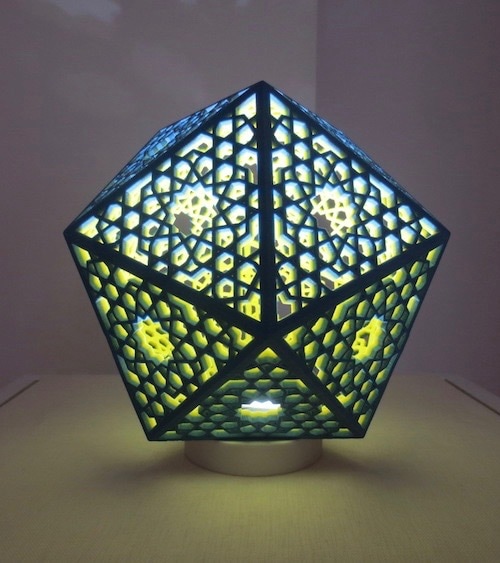

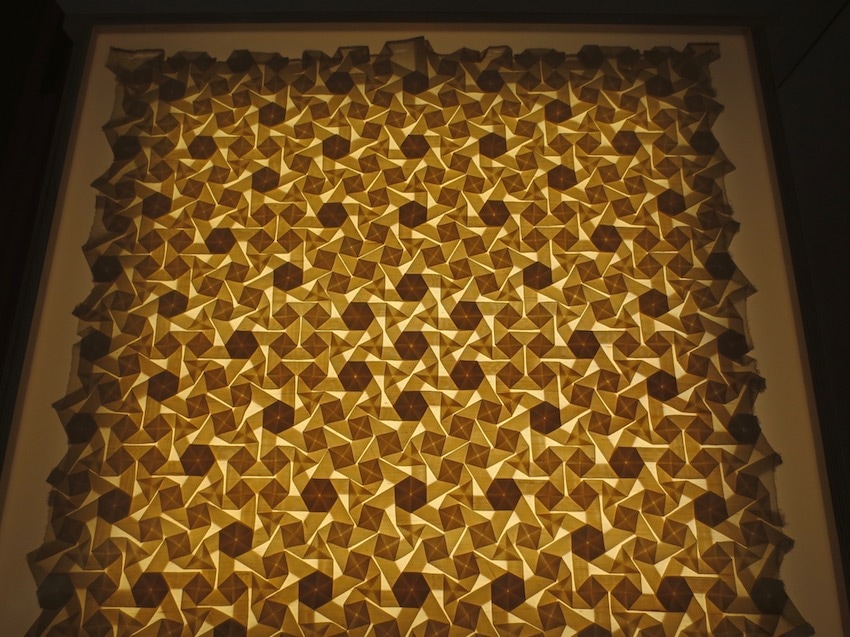

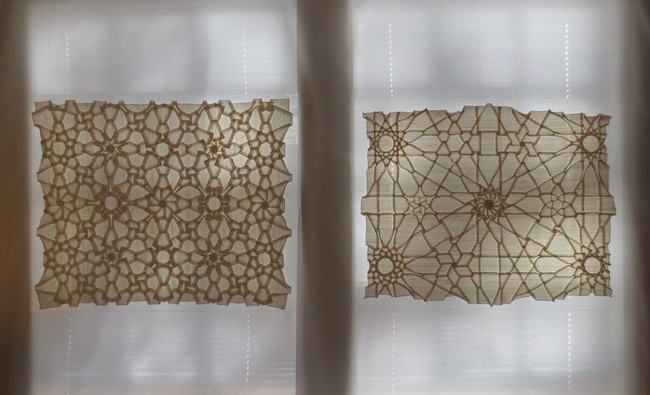

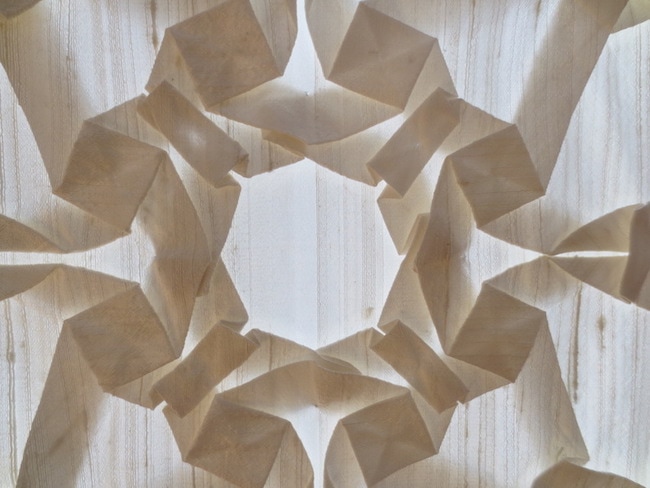

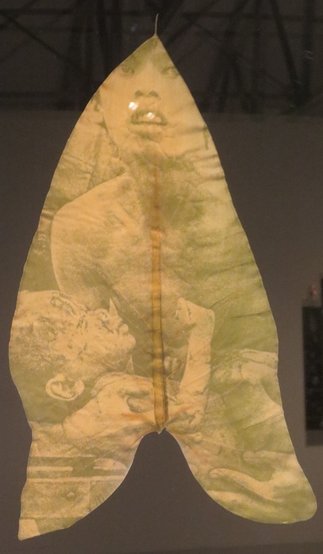

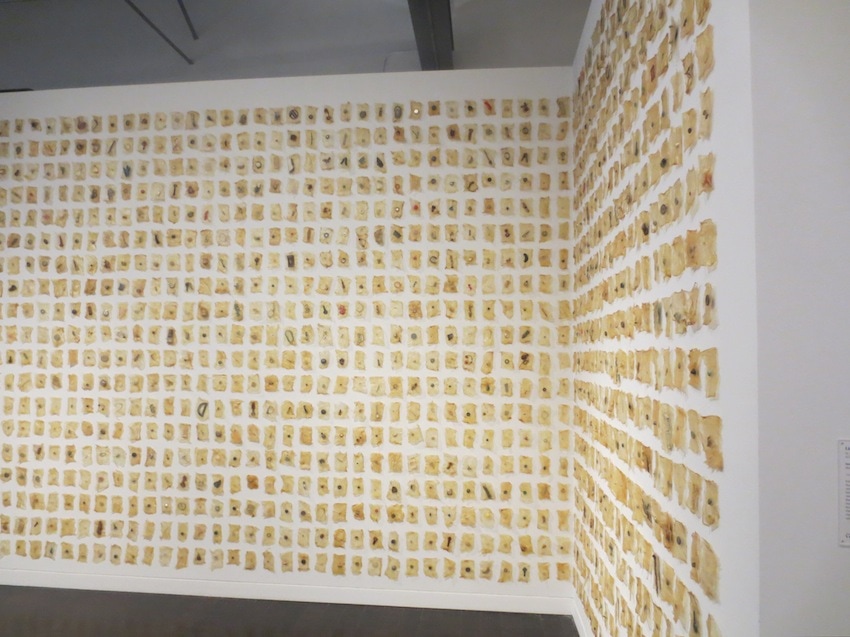

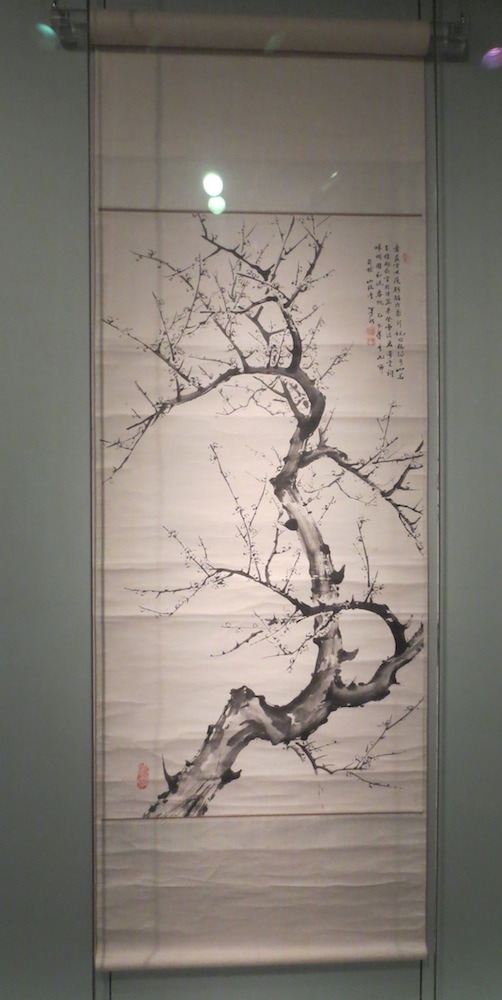

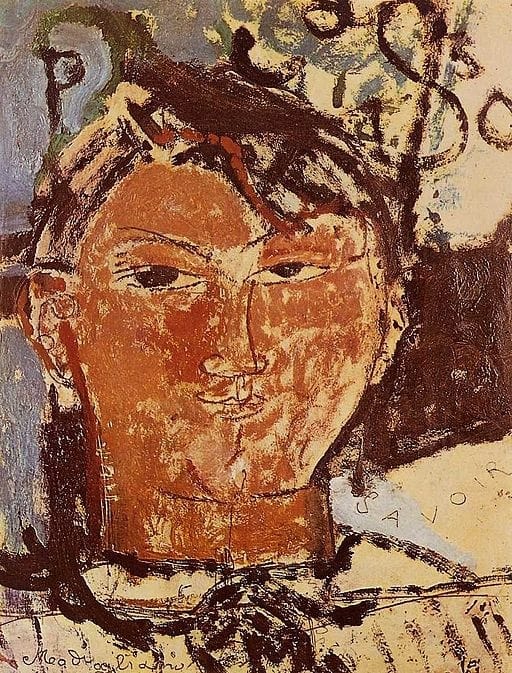

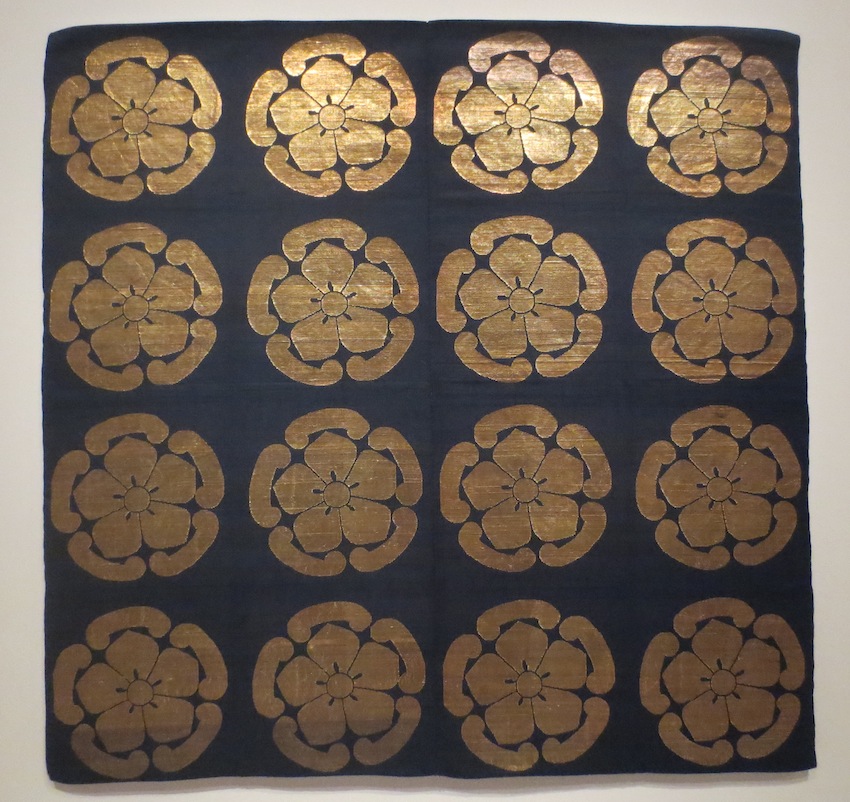

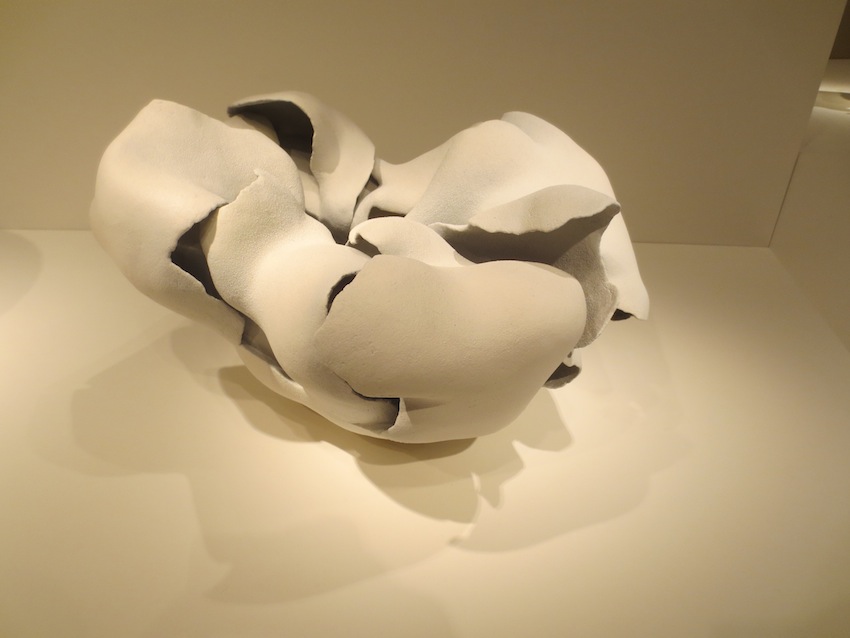

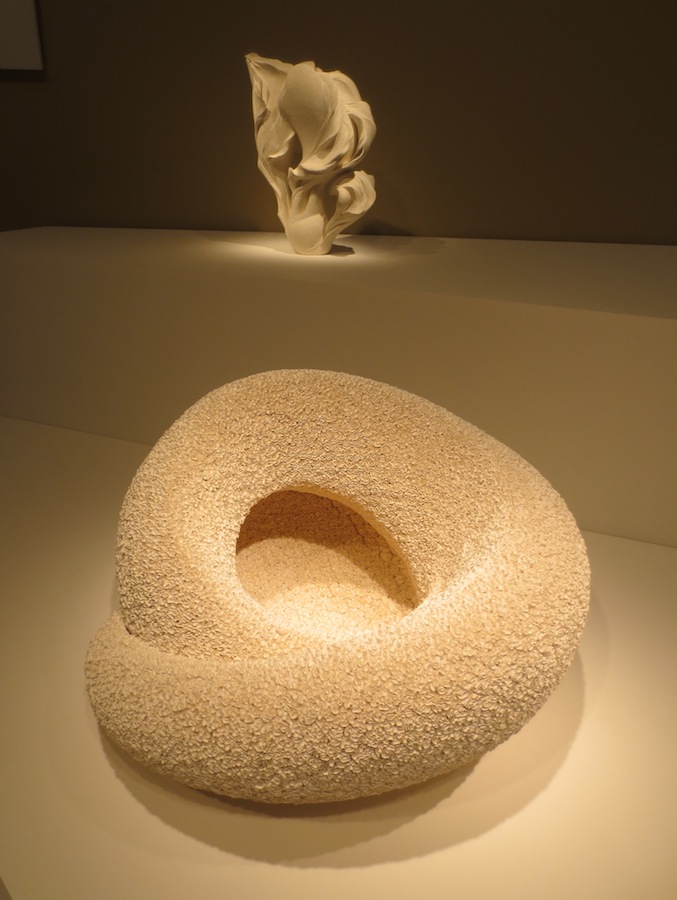

It was in the 1920s, when nobody had time to reflect, that I saw a still-life painting with a flower that was perfectly exquisite, but so small you really could not appreciate it. … I decided that if I could paint that flower in a huge scale, you could not ignore its beauty.

O'Keeffe's words strike me as the best reason for enlarging the tiniest nuances. It's what enables us to see and appreciate the fantastic art that is Nature itself.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed